Only You Can Prevent the End of History

This site offers excerpts from the concluding chapter of Re-Collection: Art, New Media, and Social Memory, a book on new media preservation by Richard Rinehart and Jon Ippolito.

This site offers excerpts from the concluding chapter of Re-Collection: Art, New Media, and Social Memory, a book on new media preservation by Richard Rinehart and Jon Ippolito.

This book can't, and won't, prescribe a cure for every strain of technological or cultural obsolescence--those cures are as much a moving target as the technologies themselves. Instead, we've tried to offer an approach meant to outlive the examples we marshal to illustrate it.

If you care about the survival of new media culture, you can start right now to adopt this approach. We offer here a twelve-step program that should get us all on track. Click on a profession or icon to learn more.

1. Curators: Update Your Acquisition Policy

![]() Implement and test some of the ideas presented earlier in this book. Despite calls to action, institutional response has been slow and scattered. Every museum, archive, or arts organization that deals with new media culture can help. You don't have to have specially trained staff or a big grant to do something; even baby steps would move us all forward.

Implement and test some of the ideas presented earlier in this book. Despite calls to action, institutional response has been slow and scattered. Every museum, archive, or arts organization that deals with new media culture can help. You don't have to have specially trained staff or a big grant to do something; even baby steps would move us all forward.

a. Revisit your institution's collection policies. Don't assume, because your institution already collects video, that you've got new media covered. What needs to change?

b. Interview artists whenever you commission or collect a work of new media. Ideally, you'd use the Variable Media Questionnaire, or another tool based on an appropriate standard like the Media Art Notation System, that will prompt questions that have been vetted in a larger community. But if you can't do any of that, just sit with the artist and ask her what she would like to see happen when her work is recreated 50 years from now. Turn on your smartphone camera and record it. Take notes on the back of the café napkins.

c. When you commission or collect new media art, put some language in the agreement that outlines who has the right to recreate or restage the work, and under what parameters (see (b) above).

d. Add 20 percent to the bottom line of your acquisition budget for each work to be put in a variable media endowment reserved for the costs of future migration, emulation, and other efforts to keep the work alive.

e. When collecting new media, don't automatically demand exclusivity or limited runs. Explore alternate models with the artist. Co-collect a work with several other institutions and share the cost and responsibility while increasing access and chances of successful preservation.

f. Develop a source code escrow that protects an artist's rights while she is alive, but releases her work to the public once she is gone.

g. Obtain the help of external communities, or at least look to them, for new models. How could your museum tap into the gamer community to help preserve a work by Cory Arcangel?

2. Conservators: Move out of the Warehouse and into the Gallery

![]() Go beyond storage to test the migration, emulation, and reinterpretation of new media artworks. Spend less money on crates and climate control, and more on funding the process of creating, and recreating, art. Rotate your collection shows as often as possible, because exhibiting a work renews it more thoroughly than any inventory or condition check.

Go beyond storage to test the migration, emulation, and reinterpretation of new media artworks. Spend less money on crates and climate control, and more on funding the process of creating, and recreating, art. Rotate your collection shows as often as possible, because exhibiting a work renews it more thoroughly than any inventory or condition check.

And the next time you exhibit a slightly worn new media artwork in a gallery, museum, or festival like the ZER01 media art biennial, work with the artist to try one of these strategies. Document your findings and share them with all of us. Don't be afraid to talk about failures; the cultural heritage community could learn from the sciences that even negative results contribute to knowledge. The Guggenheim picked up the ball with the exhibition "Seeing Double" in 2004; DOCAM's annual conferences ran with the idea from 2005 to 2010; ZKM and its partners ran still further with their exhibition "Digital Art Conservation" in 2011. Complete your leg of the race.

3. Archivists: Modernize Your Metadata

![]() Further research, test, and agree upon metadata and documentation standards that we can all use. Standards help us by prompting us to ask the right questions, and they help us to share the answers. The Media Art Notation System (MANS) is one early attempt to articulate what is required from a metadata standard specifically for new media art and then to see how those requirements would play out as a real-world standard.

Further research, test, and agree upon metadata and documentation standards that we can all use. Standards help us by prompting us to ask the right questions, and they help us to share the answers. The Media Art Notation System (MANS) is one early attempt to articulate what is required from a metadata standard specifically for new media art and then to see how those requirements would play out as a real-world standard.

a. Feel free to copy the MANS elements when you are adding a few new fields to your collection management database.

b. Use MANS as a sounding board to develop your own documentation standard.

c. Or, instead, consider adopting an existing metadata standard to describe your new media art collection. Keep in mind the special requirements of new media art. Your standard should make explicit the parameters not only for how the work was manifested in the past, but for how it should be manifested in the future. Your standard should allow, even prompt, multiple memories of the work. More detailed requirements were outlined in chapter 5.

d. Don't get hung up on the bells and whistles of metadata that enable features that no one is using; be practical. It's more important to document and preserve the art now than to work on a standard for ten years. Look around at how your potential standard is actually being used and adapt the standard appropriately. Share your adaptation and your results.

4. Collection Managers: Renovate Your Database

![]() Purchase, build, or find for free software tools that will allow you to gather together everything you'll need to preserve new media collections: the artist interview, alternate memories, original source files, other documentation such as video or artist emails, and descriptive notes about each component of the work. (The author, programmer, or legal rights might be different for each component of the work; don't assume that one blanket "copyright" or "artist" field in a database will always cover the entire artwork.)

Purchase, build, or find for free software tools that will allow you to gather together everything you'll need to preserve new media collections: the artist interview, alternate memories, original source files, other documentation such as video or artist emails, and descriptive notes about each component of the work. (The author, programmer, or legal rights might be different for each component of the work; don't assume that one blanket "copyright" or "artist" field in a database will always cover the entire artwork.)

a. Don't become daunted by the complexity of some museum tools. If need be, this back-end tool could just be a simple FileMaker database with fields that look like MANS elements or Variable Media Questionnaire questions.

b. If you build a tool, share it.

c. Look for tools that have already been developed. The Forging the Future project hosted at the University of Maine has a suite of free databases waiting for you.

d. Commercial developers of collection management tools for cultural heritage, take note. Be the first on your block to say that your system can fully accommodate new media art.

5. Institutions: Start Collecting New Media

![]() Build repositories of digital culture. Once you have one new media artwork in your care, you have a collection. Build it a home. There are detailed guidelines for creating digital repositories in the Open Archives Information Standard documentation.

Build repositories of digital culture. Once you have one new media artwork in your care, you have a collection. Build it a home. There are detailed guidelines for creating digital repositories in the Open Archives Information Standard documentation.

a. Again, don't get hung up on details while your bits die. Prototype and iterate; you'll get better each time and you'll have saved an artwork by starting early.

b. Create digital repositories that are attached to curatorial programs (such as the Walker Art Center's Digital Art Study Collection), or repositories that stand apart (such as Rhizome's Artbase), or repositories that act as production sites (like Still Water's The Pool).

c. Look for tools made specifically for this purpose such as ccHost, an opensource tool used to create the open-source music repository ccMixter.

d. Open your system to allow memory to seep through its pores both ways, so that official, institutional memory is shared with viewers and at the same time they contribute alternate memories of the work. Maybe viewers will contribute their remixes or entirely new works to the archive.

6. Programmers: Connect Data across Institutions

![]() Link these repositories of digital culture together to create a global network of digital primary evidence that exists at the tips of the world's fingers. Make this distributed database scalable and inclusive to leverage the wisdom of the crowd, expose and share undiscovered cultural artifacts, and ensure the maximum chance of these artifacts surviving.

Link these repositories of digital culture together to create a global network of digital primary evidence that exists at the tips of the world's fingers. Make this distributed database scalable and inclusive to leverage the wisdom of the crowd, expose and share undiscovered cultural artifacts, and ensure the maximum chance of these artifacts surviving.

a. Help flesh out the idea for an Interarchive, discussed earlier.

b. Consider registering or integrating your own repository with Forging the Future's Metaserver or contributing to a union database of digital assets like OAISter as a way of sharing your content and maximizing knowledge.

c. Consider allowing your own digital repository, or parts of it, to be cloned by others to maximize its chances of survival through redundancy and shared responsibility.

d. Make participation in this distributed database very easy, even for small institutions. Consider how an archive would participate if it had a staff of four, no dedicated IT specialist, and no funds for specialized tools. How would an individual artist or scholar participate directly?

e. Build this distributed database so that it uses widespread existing Internet tools and knowledge; it should be as easy to contribute to the database as it is to build a blog or a webpage. Consider the Open Library as an example.

7. Lawyers: Help the Arts Find Progressive Approaches to Copyright

![]() The Canadian Heritage Information Network commissioned a white paper, Nailing Down Bits: Digital Art and Intellectual Property, that reported findings on research and professional interviews related to digital art and the law. This paper concluded with a research agenda that could serve as a useful starting point for others. In addition to opining, surveying, and theorizing, Nailing Down Bits argued that we need to test how new media art and the law interact in the real world. When asked for advice on the best strategy to do this, staff of the Creative Commons answered that the arts community should build repositories of new media art in order to play through the legal issues (see numbers 1–6 above). Experimentation and precedent are more useful than preemptive guesses. Jump in. Some other steps might include:

The Canadian Heritage Information Network commissioned a white paper, Nailing Down Bits: Digital Art and Intellectual Property, that reported findings on research and professional interviews related to digital art and the law. This paper concluded with a research agenda that could serve as a useful starting point for others. In addition to opining, surveying, and theorizing, Nailing Down Bits argued that we need to test how new media art and the law interact in the real world. When asked for advice on the best strategy to do this, staff of the Creative Commons answered that the arts community should build repositories of new media art in order to play through the legal issues (see numbers 1–6 above). Experimentation and precedent are more useful than preemptive guesses. Jump in. Some other steps might include:

a. Arts organizations that build repositories of new media art can partner with a law school program, professor, or legal clinic. The repository provides interesting new legal research opportunities for the students, while they provide much-needed legal analysis.

b. Artists working in new media are encouraged to consider the legal disposition of their artworks. Artists may consider licensing their work through Creative Commons or the Open Art License mentioned in chapters 7 and 10. Artists can also consider and then articulate in written guidelines who is allowed to remix their works now and who will be allowed to reinterpret and reconstitute them in the future. If you are an artist, don't wait for a collector to interview you. Just include your instructions with the artwork, wherever it goes.

c. Institutions such as museums are often caught in the middle of copyright issues, between the artist/creator and the public/user. But institutions also originate valuable knowledge themselves, such as records, video and photographic documentation, and educational texts or scholarly essays. These institutions can release their own content through open licenses to maximize the benefit to the public.

d. Law is often about interpretation; this is especially true in the arena of digital copyright, which lacks a long history of case law. Lacking precedent, courts may judge a case based on established community practice. That means that in an unclear case, defendants who are merely following the practice of their peers, in good faith, would be judged with more leniency. Since cultural community practice is still emerging, it would be of mutual benefit to establish liberal rather than restrictive common copyright practices. This means that whenever artists or museums make liberal copyright decisions, they help shield themselves and others in the future. This is illustrated in a recent Canadian Supreme Court decision which found that the consistent application of a written fair-dealing policy was prima facie evidence of the practice of fair dealing and that the burden of proof was placed upon the plaintiff publishers to dissuade the courts otherwise.

8. Creators: Save in as Open a Format as Possible

![]() Protect your content. Back up your culture. Aim for long life if not immortality.

Protect your content. Back up your culture. Aim for long life if not immortality.

a. Whenever possible, save your work as uncompiled (ASCII) text or code. If you must use compiled code, save the original source file as well as the compiled one.

b. Be selective in what you preserve. You are most likely to preserve what you have a good reason to look at again.

c. Back up in multiple locations, both local and online.

d. Post/back up your work to open archives (Internet Archive) rather than proprietary ones (YouTube).

e. Avoid compression if possible.

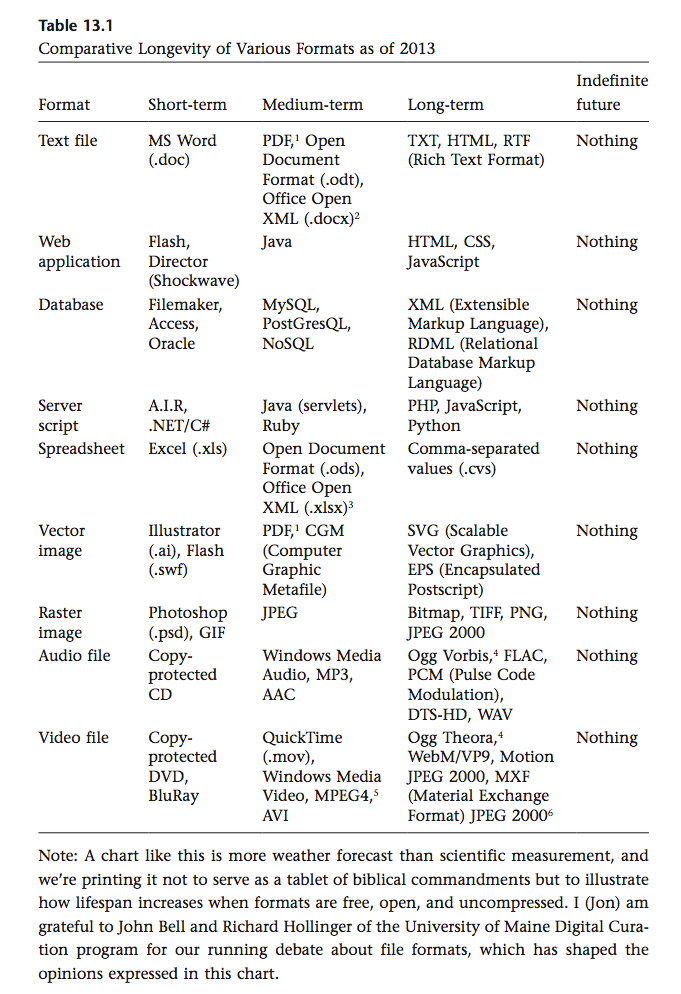

f. Avoid proprietary formats, especially ones with any form of digital rights management, in favor of free and open standards. (Our best guesses on format longevity appear in table 13.1.)

f. Avoid proprietary formats, especially ones with any form of digital rights management, in favor of free and open standards. (Our best guesses on format longevity appear in table 13.1.)

9. Dealers: Invent New Economic Models

![]() Research, model, and test how new media art interacts with the art market and other economic environments. Due to the legal, social, and technical complexities that attend new media art, collectors are sometimes understandably hesitant to buy this work. That forces new media artists to experiment with alternate economic models, but it also removes a time-tested source of support for individual new media artists and indeed for a whole genre of creators. Some brave models exist. For instance, the Catherine Clark Gallery in San Francisco and the Bitforms Gallery in New York have successfully sold new media art and have developed methods for continuing to do so. Caitlin Jones pioneered the use of variable media questionnaires in new media acquisitions for the Bryce Wolkowitz gallery.

Research, model, and test how new media art interacts with the art market and other economic environments. Due to the legal, social, and technical complexities that attend new media art, collectors are sometimes understandably hesitant to buy this work. That forces new media artists to experiment with alternate economic models, but it also removes a time-tested source of support for individual new media artists and indeed for a whole genre of creators. Some brave models exist. For instance, the Catherine Clark Gallery in San Francisco and the Bitforms Gallery in New York have successfully sold new media art and have developed methods for continuing to do so. Caitlin Jones pioneered the use of variable media questionnaires in new media acquisitions for the Bryce Wolkowitz gallery.

a. Gallerists and private collectors need to be part of the conversation around preserving new media art. Private collecting not only provides one form of tangible support for artists, it also constitutes an additional sphere for preservation. We can come together in professional forums and individual partnerships to develop equitable models for how private collecting can coexist with public service and even open-source practices. (For example, no more self-destructing DVDs.)

b. Limiting the edition for a duplicable work to three or five instances may help you jack up its price, but remember how poorly digital rights management has served the entertainment industry. You're more nimble than Sony or Time Warner--invent a creative financing scheme that doesn't restrict future access to the work. Otherwise, artificial scarcity in the short term will lead to innate scarcity in the long term.

c. For their part, creators should continue to explore additional economic models such as art subscriptions. Some models can succeed independently of the art market; artists like Scott Snibbe have sold inexpensive works in high volume for mobile devices through commercial music and software channels.

10. Funders: Fund the Preservation of Born-Digital Culture

![]() The NEA, NEH, and others have generously funded projects, including many of those mentioned in this book. Still, much funding continues to be devoted to building giant online databases of scanned paper documents and pictures of paintings. These are invaluable for research, but while we're researching our past using new media, our contemporary culture, created using those same media, lies dying. How much of the original $99 million dollar Congressional allocation for the preservation of digital culture (NDIPP) is going toward the problem of preserving digital art, or any born digital culture for that matter

The NEA, NEH, and others have generously funded projects, including many of those mentioned in this book. Still, much funding continues to be devoted to building giant online databases of scanned paper documents and pictures of paintings. These are invaluable for research, but while we're researching our past using new media, our contemporary culture, created using those same media, lies dying. How much of the original $99 million dollar Congressional allocation for the preservation of digital culture (NDIPP) is going toward the problem of preserving digital art, or any born digital culture for that matter

a. Large funders like foundations and government agencies could create programs, no matter how small to begin with, that deal with the preservation of born-digital material.

b. Funders could help everyone by funding risk and new approaches. It's safer of course to fund time-honored methods, but, as this book has tried to make clear, if we continue our old practices, our new culture is doomed. Again, even failure can produce new knowledge.

c. Not just large funders but small ones on the level of individual galleries, museums, and sponsors can help as well. When you next commission a work of new media art, consider how your investment will serve the public in the long term as well as for the short-term exhibition or program. You might consider incorporating elements into your agreements that stipulate that the commission be available for remix, if only on a local level. (The V2 organization in Rotterdam included a requirement that work produced in their lab on one of their fellowships be kept in the lab and made available to future fellowship artists for remix.) A university museum could require a similar stipulation that served just their campus (if not the world). It's a start.

11. Academics: Educate, Engage, Debate

![]() This book is one small attempt to further our shared conversation around new media, preservation, and social memory. We need much more.

This book is one small attempt to further our shared conversation around new media, preservation, and social memory. We need much more.

a. If you are at a university, consider sponsoring a program or department like NYU's innovative Moving Image Archiving and Preservation Program, Avignon's Laboratoire des Médias Variables, or the Digital Curation online program at the University of Maine. There aren't enough around, and it's a chance to claim a niche while serving a need.

b. We need programs like the one above, but which focus on or include a significant component oriented specifically at new media art.

c. If you are at a museum, train your next preservator with a fellowship like the Guggenheim's Variable Media Fellowship. Or consider a public forum on the topic, like the Berkeley Art Museum's "New Media and Social Memory" conference. Use this as an opportunity to engage with private collectors or law schools, as mentioned above.

d. In addition to individual schools and universities, larger umbrella organizations such as the American Alliance of Museums, the Museum Computer Network, and College Art Association can serve as clearinghouses for information and professional development around new media preservation.

e. Beyond the world of art and museums, create new conversations and new partnerships with others who also struggle with new media preservation: government agencies, libraries, industry, and entertainment.

12. Historians: Challenge Conventional Wisdom about Social Memory

![]() As we said at the beginning of this book, new media have created a crisis in remembering that provides both an impetus and an opportunity to revisit the models and practices of social memory. This crisis is not limited to the art world. We need to foster and reward research on the theoretical, artistic, and social implications of the interplay of new media and social memory. We cannot significantly alter entrenched institutional practices without tackling the historical attitudes and discourse behind them, so both the practical and the theoretical are important here. Review the museological model for preservation. Put people--creators and collectors of artifacts--at the center. Question the current configuration of institutions (do the three primary types of cultural heritage institutions--museums, libraries, archives--remain the primary types we need today

As we said at the beginning of this book, new media have created a crisis in remembering that provides both an impetus and an opportunity to revisit the models and practices of social memory. This crisis is not limited to the art world. We need to foster and reward research on the theoretical, artistic, and social implications of the interplay of new media and social memory. We cannot significantly alter entrenched institutional practices without tackling the historical attitudes and discourse behind them, so both the practical and the theoretical are important here. Review the museological model for preservation. Put people--creators and collectors of artifacts--at the center. Question the current configuration of institutions (do the three primary types of cultural heritage institutions--museums, libraries, archives--remain the primary types we need today